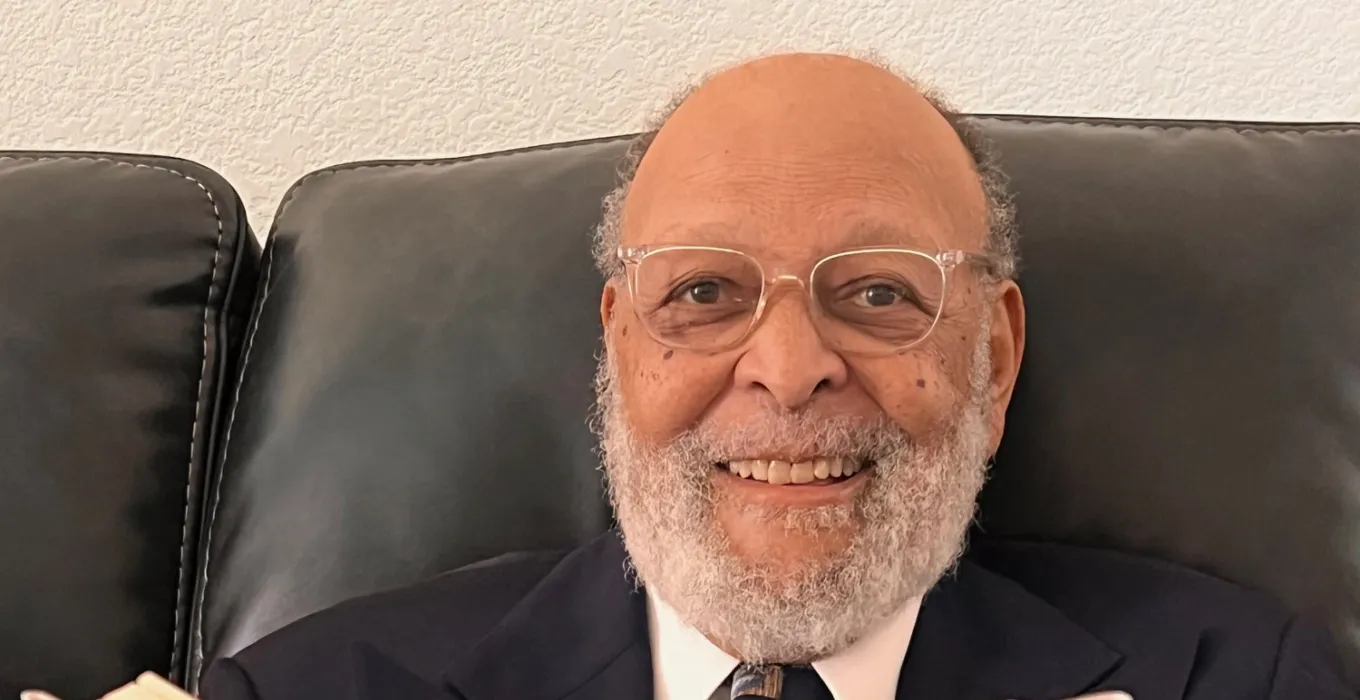

The Peaceful Retiree Monthly Interview: Marvin Smith

The Peaceful Retiree Monthly Interview: Marvin Smith

Tom Marks (TM): Marvin, I begin all of my interviews with the same question: Tell us your origin story.

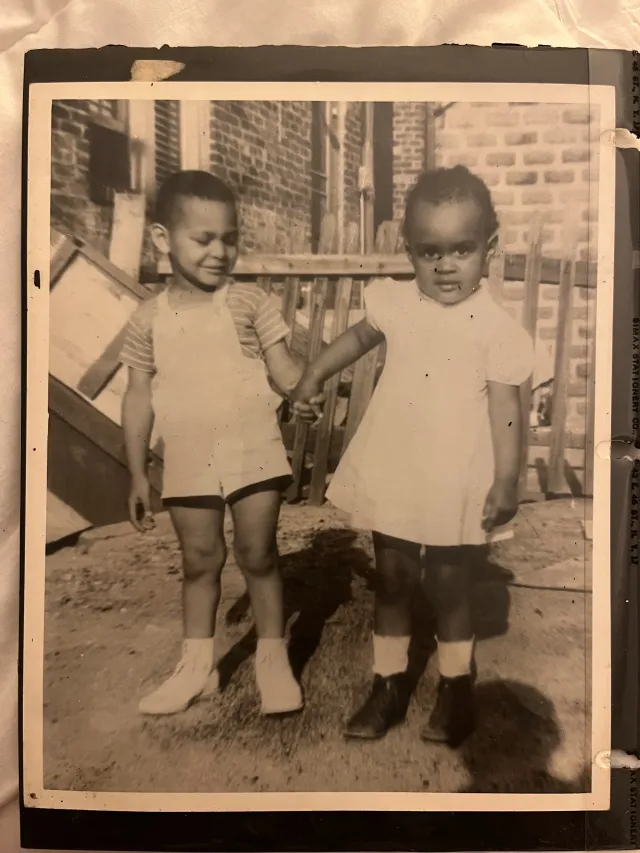

Marvin Smith (MS): I was born in 1942 in Glen Cove, New York which is on the North Shore of Long Island. Not long after, I moved to Queens where I was raised by grandmother, Mattie Crowder, because my parents were working Monday through Friday, basically day and night, for a family living on The Island. My father was a chauffeur and my mother was a caretaker for the family. My parents lived in a carriage house on their employer’s property and that’s why I was raised in the city.

TM: At what point did you realize you might be different from others?

MS: I was about 5 years old. On Long Island, I never felt particularly endangered as a Black kid, and even in the city, I was raised in a type of “Archie Bunker” row house where you could literally touch the house next door to you. Although I knew I was different and certainly felt out of place, again, I never felt unsafe.

TM: Was there a time when that changed?

MS: It changed when I went to high school. Up until then, and as I reflect on my life, I wasn’t overly aware of the hardships of people of color, but in high school, I definitely experienced what I refer to as “subtle discrimination.” Over the years, in periods of reflection, it wasn’t subtle at all. In fact, it was during my senior year, and then for a time thereafter, where discrimination became more pronounced.

TM: Can you give us a few examples of the types of discriminatory behavior you experienced?

MS: I wasn’t a particularly great student in high school, not bad, but not great either. Back then, my focus was on playing football, running track, and owning a car. That’s what I wanted, and I wanted to make some money so I could maintain my car, keep it spotless, and fine-tuned. Obviously, that’s something my dad taught me in his job as a chauffeur. Now, I tell you this because this was the prelude to my initial experiences with both discrimination and the need to work hard.

Ultimately, I buckled-down, elevated my grades to Bs and B-plusses, and then tried to get into college. That’s where it started to get tough. I had my eyes set on a school called C.W. Post, which, I believe, is now part of Long Island University. Without going into too much detail, they made it extremely difficult for Black students, including me, to apply and be accepted. They demanded testing, and then more testing, and this wasn’t necessarily the protocol or process for White students. I don’t remember being overly bitter because that’s just the way things were, the sign of the times, but looking back on it, particularly in an educational setting, it was pretty demeaning.

TM: So what did you do?

MS: I went to work in the local welfare office mopping floors, cleaning bathrooms, and doing it in the early hours before the employees arrived for their morning shift. To this day, I remember the mop they gave me, it was enormous; I had never seen anything like it. I fell further and further behind the other “office boys” who were already experienced with the intricacies of handling giant mops. So I literally practiced my mopping skills, and when I was done practicing, I practiced some more. And then a funny thing happened, I got so good and so fast at mopping that the old-timers in the welfare office told me to slow down and take it easy; they were so fearful that I was setting a new standard that they’d never be able to match. It was one of my first lessons about the importance of practicing and hard work.

TM: And then something happened.

MS: Yes it did. I met a man who took a liking to me named, Irv Flemingbaum. He told me in no uncertain terms that I needed to go to college, and I explained to him that I was rejected at C.W. Post. Without missing a beat, Irv replied that it was only one college that rejected me, but there were plenty of others. So he convinced me to take more tests and he showed me how to apply for loans and other forms of assistance. But in the early 1960s, there just weren’t many opportunities for Black students, except at HBCUs (Historically Black Colleges & Universities). I had a few relatives in Richmond, VA so I enrolled at Virginia Union University and graduated there in 1967.

TM: And what did you learn?

MS: Well, I learned plenty. As a matter of fact, when companies would come to the university to hire students for jobs, 100 students would come for interviews, and not one student would get a job. That’s one thing I learned. And the other thing I learned, obviously, was that it was going to be damn difficult getting a good job as a Black man.

TM: But you persisted.

MS: Of course I did, I had to. Ultimately, I drove up to New Jersey for an interview with Westinghouse and they offered me a job right on the spot. I was hired as an Industrial Relations Assistant where I would meet with employees in the factory and listen to their ideas on how the company could save money. If their ideas were implemented, and actually did save the company money, employees would get 10% of the savings, and it was my job to calculate what those savings were.

TM: Why do you think Westinghouse offered you a job on the spot?

MS: Well, it wasn’t from my advanced mopping skills, but it was, in part, because of the interactions I had fine-tuned as a young boy on my paper route. More specifically, I had to get people to pay me when some people on the route had no intention of paying me at all. I also had a knack for talking to people, interacting with them, and being a good listener which was a characteristic I learned from my father.

TM: So what was your career trajectory after Westinghouse?

MS: My time at Westinghouse taught me that I could be successful working in a corporation. I actually went back to the original person who hired me, and he told me that Polaroid in Cambridge, MA was hiring in their camera division. I was hired there in Organizational Development and stayed with Polaroid for 3 years. While I was at Polaroid, I found out that the company would pay for my master’s degree, and I took them up on the offer, but before I completed my degree, I learned about an accelerated management program at General Electric and I accepted a position at GE, but never completed my masters. That was a lifelong mistake. I stayed at GE for about 5 years before I moved on to my next challenge.

TM: And that was?

MS: I joined a company called Synectics where I stayed for 30 years. It was a company that managed process innovation and I became a corporate Vice President. While I was there, I put aside many concerns in my mind, and the minds of others, that a Black man could be a corporate leader. I belonged there, but only to a point. I knew that they were forever checking and double-checking my work and credentials, and I also understood that the upper echelons of leadership and ownership, at that particular time, were going to be improbable. It was okay for me to have a certain type of job, but not THE job.

For the rest of my life, I have referred to this as the “Black Tax”, the price we paid to succeed, but also the price we paid to never be as successful as we were meant to be. This was confirmed to me one day when a man said to me, “If I hire a Black man, and YOU make a mistake, I’ll lose my job.” After that, I did consulting work with CEOs and facilitated CEO Round Table discussions and workshops, but by that time I was already 65 years old and not as ambitious as I once was.

TM: Okay Marvin, tell us some life lessons.

MS: Most of what I learned was through practical experiences. I do remember my mother and father telling me that being a loud and obnoxious Black man wasn’t going to get me very far, but if I spoke to people the way they should be spoken to, if I was a good listener, and if I understood that people and their opinions were important, there would be far more opportunities for me. I also learned that I should have completed my master’s degree. And finally, I would have been wise to have looked for a niche that I could have specialized in, opened my own business based on that research, and not always joined others, but more suitably, carved my own path forward. I think that applies to a lot of people.

TM: In the end, how much did being a Black man hold you back?

MS: I think it was indisputable that it held me back, but at the same time, it was never my focus, and I’m glad it wasn’t. If that had become my calling, I would have been bitter, and that would have held me back even more. The notion of the “Black Tax” made me work harder and practice longer. But it brought clarity to the notion that I had let things slide for so long. In fact, I was in Newport Rhode Island with my wife Phyllis and we were strolling along the Cliff Walk and I was stepping aside to allow White people to pass by. I realized then that I was showing deference to them when I certainly didn’t need to. It takes a long time to overcome “stepping aside”.

TM: I know our readers are waiting with great anticipation about your thoughts on retirement and how to transition into it.

MS: It’s so simple which is why it can seem so complex. Get a clear vision of where you’re going and what you want to do before you retire. What kind of travel and recreation you want to do is a good place to begin. It’s mandatory to refresh your listening skills with younger people and never forget to ask permission to give advice before you actually do give advice. Be a resource as someone who gets called on, not someone who’s forever spewing guidelines, principles, and lessons.

Volunteer if you can, your knowledge is valuable, but it can be fleeting. I’m so fond of the days, not that long ago, when I was able to talk to groups like The 100 Black Men, it kept my mind sharp, but now I’m more consumed with taking care of my health and my body. Lastly, use a low level of judgement on people – and yourself. If you don’t it can lead to suffering and bad interactions. It’s harder to maintain meaningful relationships in retirement the more judgmental you are.

TM: Thank you so much for your wisdom and insights, Marvin.